Meningioma account for over 50% of all neoplasms of the CNS in cats and are typically seen in older cats over 10 years of age. Meningioma arise from neoplastic arachnoid cap cells and the majority being unilateral cerebral hemispheric lesions with a broad flat base. However, alternative locations (eg. skull base, tentoral) and alternative meningeal attachments (eg. Pedunculated or total/en plaque as opposed to broad based attachment) can be seen; location and meningeal attachment types have implications for the ease of surgical management.

Earlier this month an 11 year old feline patient having undergone surgical management of a meningioma, has returned for her 6 month post-operative recheck and she continuing to have a normal neurological examination at this time. She presented in June with a gradual decline in her demeanour and activity levels with an acute decline in her mobility. Examination in June had shown loss of the left sided menace response and response to proprioceptive testing on the left, with compulsive pacing and circling compatible with predominately right sided forebrain dysfunction. In general, the presenting clinical signs of feline patients with meningioma will of course be influenced by the location of the meningioma, however similar to this patient, the majority of cats show signs relating to unilateral forebrain dysfunction with behaviour changes of pacing and dullness frequently seen. In contrast to dogs where seizures are the most common presenting signs with a meningioma, only 23% of cats were shown to present with seizures (Tomek 2006). The slow growing nature of the mass is reflected in the insidious onset of signs commonly seen, with the not infrequent presentation after an acute decline at the time when the intra-cranial compensatory mechanisms become overwhelmed. With feline patients therefore presenting in the later/decompensating stages, once neurological deficits are seen, the subsequent survival time is usually short.

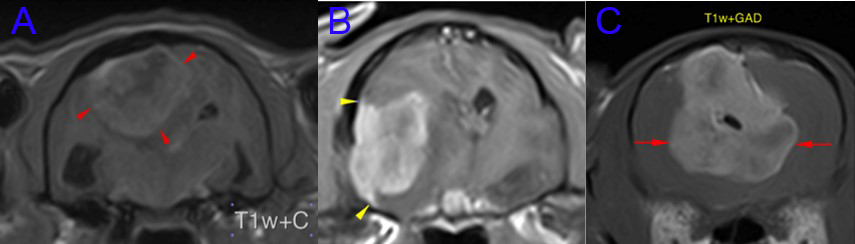

The MRI appearance will be that of an extra-axial mass with strong contrast enhancement and a heterogeneously increased T2 weighted signal intensity from the mass and any surrounding oedema. Additional features include adjacent calvarial hyperostosis and dural tail. The latter being contrast enhancement of the meninges adjacent to the mass that has been thought to either represent extension of neoplastic cells beyond the margin of the mass of the meningioma or increase vascularity of the dura mater. Brain MRI does not result in a definitive diagnosis, however since over 80% of extra-axial tumours in cats have been found to be meningioma and MRI has a very high sensitivity for detection of this tumour type in cats (98%), there can be a high level of confidence in the diagnosis. In one study it was reported the correct identification of 96% of brain tumours as meningioma using the appearance on MRI alone (Troxel et al 2004)

When the location of the meningioma is amenable to surgical treatment this would be the treatment method of choice in cats, with the additional considerations naturally including the individual client’s expectations and preferences. Below are representative MRI images of three feline patients having undergone surgical management here in the last 18 months. Surgical treatment was the treatment of choice with all three meningioma locations, however the very ventral location of the tumour in case B and the pedunculated meningeal attachment in case C (the patient described in this report) having a negative influence on the ease of surgical accessibility.

Compared to dogs, the histological appearance is more stereotyped in cats and are most often meningotheliomatous or psammomatous types, being fibrotic and much less likely to show infiltration into the brain tissue. Several reports of prognosis with surgical management exist. These include descriptions of the early post-operative mortally being approximately 19%. Survival studies have reported 78% of the cats having no clinical signs of tumour recurrence of a median of 27 months and another showing 50% survival at 2 years post-surgery. The outcome of surgical treatment may depend upon the location and ease of removal, and also proximity to critical structures in particular the sagittal or cavernous sinuses (Gordon et al 1994, Gallagher et al 1993)

The use of steroids in the pre-operative and initial post-operative period can improve the clinical signs through several mechanisms. Steroids can directly decease the permeability of tumour capillaries decreasing blood supply to the tumour and decreasing tumour volume, reducing intra-cranial pressure and brain oedema. Explains the indications for steroids in cases where surgical treatment is not chosen.

The patient described in this report is no longer receiving steroids, however, continues to receive a low dose of phenobarbitone since seizures developed in the few days between diagnostics and surgery. Extended post-operative antibiotics were prescribed since the rostral extent of the mass necessitated access via the frontal sinus. She is due to return to us for her next assessment in 3 months’ time.

References

Tomek A, Cizinauskas S, Doher M, et al. Intracranial neoplasia in 61 cats: localisation, tumour types and seizure patterns. J Feline Med Surg 2006;8:243-253

Troxel MT, Vite CH, Massicotte C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging features of feline intracranial neoplasia: retrospective analysis of 46 cats. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18(2):176-189.

Gordon LE, Thacher C, Matthiesen DT, et al. Results of craniotomy for the treatment of cerebral meningioma in 42 cats. Vet Surg 1994;23(2):94-100 (also 19% mortality)

Gallagher JG, Berg J, Knowles KE, et al. Prognosis after surgical excision of cerebral meningioma in cats: 17 cases (1986-1992). JAVMA 1993;203(10):1437-1440.