A four-year-old female Labrador Retriever was first presented to SCVS in July 2017. The owners reported that for four days, she was depressed, vomited intermittently and her gait became progressively uncoordinated. One day before presentation at SCVS, she was seen by her RVS and pyrexia was identified.

The neurological examination showed a patient with normal mentation and behaviour. Posture was normal apart from the tendency to lean to the left side. Gait evaluation showed mild proprioceptive and vestibular ataxia and a mild tetraparesis that were both more pronounced on the left side of her body. Postural reactions were delayed on all four limbs with the left sided limbs worse than the right. Cranial nerve examination showed a right sided ptosis, an intermittent right-sided positional strabismus and an ataxic vestibulo-ocular reflex when the head was turned to the right side.

The neuro-anatomical localisation was of a multifocal lesion involving the midbrain and the brainstem. An inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) disease such as (meningo-) encephalitis of unknown aetiology or an infectious CNS disease such as protozoan infection/ bacterial infection/ viral infection were considered the most likely differential diagnoses. Other possible differential diagnoses included cerebrovascular accidents such as haemorrhagic or ischaemic infarct or neoplastic CNS disease such as a brain tumour.

Blood samples were obtained for biochemistry, haematology and a clotting profile, which were all unremarkable. Serology for infectious disease testing included Lyme disease, Toxoplasmosis, Neosporosis, Ehrlichiosis, Anaplasmosis and Angiostrongylus. All the results of the infectious diseases tested were negative.

MRI of the head was performed and the findings were consistent with multifocal intra-axial lesions affecting the thalamus and the brainstem. The findings were consistent with the presence of inflammatory or infectious CNS disease.

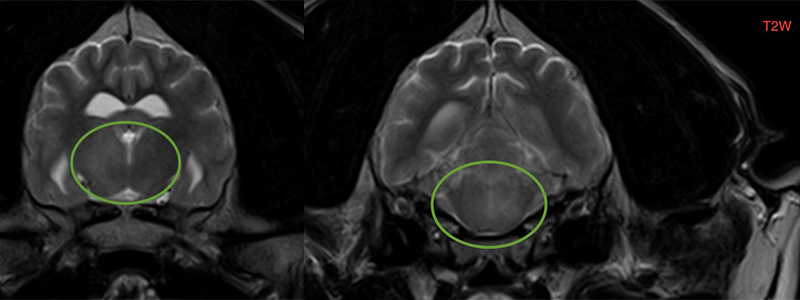

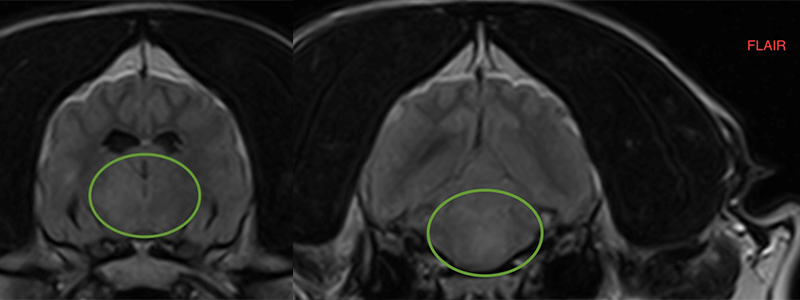

Fig. 1) T2 weighted transversal sections of the brain from July 2017. Lesions highlighted by green circle.

Right side: intra-axial ill-defined T2 and FLAIR hyperintense lesion affecting the brainstem left and right sided.

Left side: intra-axial ill-defined T2 FLAIR hyperintense lesion affecting the thalamus, right side of the thalamus is more affected.

Cisternal cerebrospinal fluid collection was performed and the results showed mild mononuclear pleocytosis. This result confirmed the suspicion of an inflammatory or infectious CNS disease. PCR testing for infectious diseases (Lyme disease, Distemper, Neosporosis and Toxoplasmosis) from cerebrospinal fluid did not detect the presence of any of those infectious agents in the central nervous system.

To control the brain inflammation, prednisolone (a corticosteroid) was started at an immunosuppressive dose and – while we were waiting for all infectious disease results to become available – with clindamycin.

As soon as all infectious diseases were ruled out, antibiotic treatment was terminated. With no infectious diseases present, an autoimmune disease was suspected to be the cause of the presenting sings.

To achieve better control of the autoimmune disease, prednisolone treatment was combined with Cytarabine, a chemotherapeutic drug, as an adjunct immunosuppressive drug. There was a very good response to this treatment and the patient was discharged after five days with a good general condition and minimal neurological deficits. At re-examination after three weeks, no neurological deficits were present.

Three and a half months after the diagnosis of encephalitis of unknown aetiology, a second MRI of the head followed by a cerebrospinal fluid analysis were undertaken to assess the success of the treatment. The MR images did not show any parenchymal changes and the CSF results returned within normal limits.

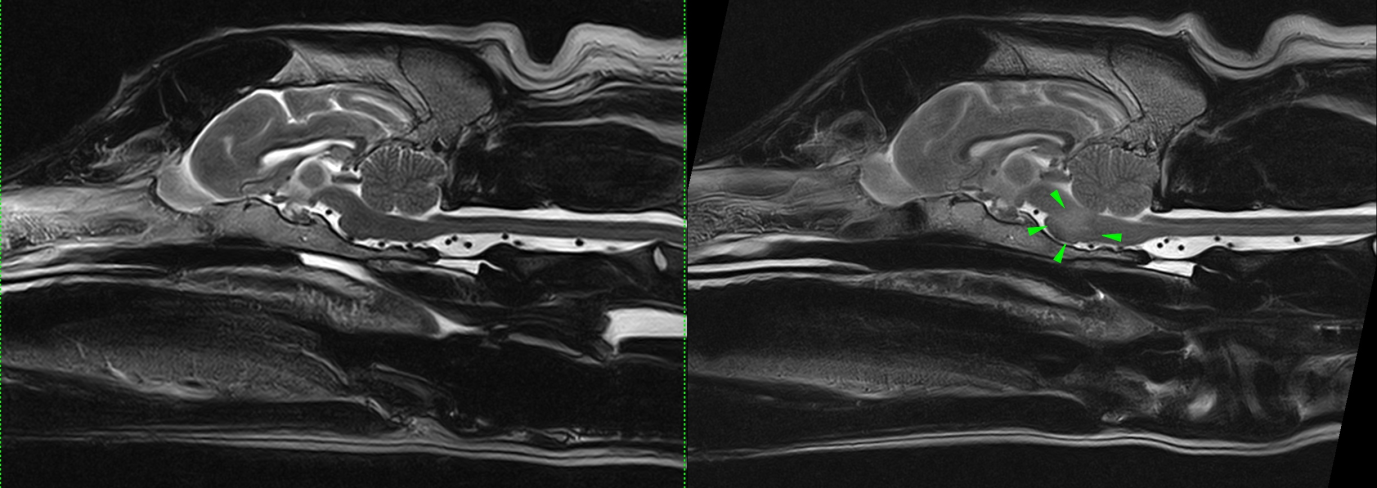

Fig. 2) Comparison of mid-sagittal T2 sections of the brain. Right side image from July 2017, left side image from November 2017. The ill-defined intra-axial T2 hyperintense lesion affecting the brainstem (green arrow heads) is no longer visible. The brain on the left side looks normal.

Calcinosis cutis and bacterial skin infection were seen as a complication of the high dose of corticosteroid treatment. This complication resolved after prednisolone was weaned off and the bacterial skin infection was treated with antibiotics. No signs of calcinosis cutis are currently present. The Cytarabine treatment is towards the end of the course.

Encephalitis of unknown aetiology belongs to a group of diseases were the causes are currently not know. Immune-mediated processes are suspected, were the immune system for reasons unknown starts attacking the central nervous system. In certain breeds like the Pug, a genetic predisposition is known. Autoimmune diseases respond to corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs like Cytarabine, cyclosporine, procarbazine, leflunomide and mycophenolate mofetil. Radiotherapy has been a successful treatment in certain patients.

Young to middle aged dogs are most often affected. While medium sized dogs and large breed dogs can be affected, most commonly small breeds like the Pug, French Bulldog, Chihuahua, Yorkshire Terrier, Maltese, Pekinese and Shi-Tzu are presented with autoimmune diseases of the central nervous system.

MRI of the head and/or spine in combination with cerebrospinal fluid analysis is commonly used to diagnose (meningo-) encephalitis of unknown aetiology. MRI findings may include T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity of the white matter, oedema of the affected parts of the brain, patchy contrast uptake in T1 post contrast images and meningeal changes. A normal MRI of the brain and/or spine does not rule out the presence of an inflammation. For this reason, examination of CSF is important in a patient were an inflammatory CNS disease is suspected. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis shows in many cases an elevation of protein and/or and elevation of white blood cells. Normal CSF results are less common but again do not rule out the presence of (meningo-) encephalitis. Underlying infectious aetiologies are ruled out by testing serology and PCR of infectious agent from blood and cerebrospinal fluid respectively. Brain biopsy would be an additional way to confirm the diagnosis but is an invasive technique that is currently not offered routinely.

Prognosis is guarded and therefore early diagnosis and aggressive treatment is paramount. If the patient responds favourably to treatment and like in this case, the recheck MRI and CSF analysis after three months is normal, the prognosis is better. Seizures and certain breeds have been associated with a poorer prognosis. Pugs often suffer from an aggressive form of encephalitis (necrotising encephalitis) that progress rapidly over three to six months and leads eventually to death.